Originally published on Medium, here.

I just read Steve Yegge’s Dear Google Cloud: Your Deprecation Policy is Killing You. I agree. It inspired the following. Apologies for the word “techie” — it’s meant to be a catch-all:

There’s a lot involved in trust and tech. There’s never been a time when a grizzled, round-shouldered older techie didn’t mistrust something or other, and a young techie didn’t think they were just being cynical.

For those carrying a touch of grizzle themselves, that mistrust is more understandable. Most mistrust seems to not be directed purely at the new or the unfamiliar — although that happens — but at the ever-alluring promise of Easy Technology.

Top secret strategy for winning

This has happened throughout the decades. Products that write code. AI that writes products. Frameworks that do all the work. Tools that are “just config”. And now we are firmly in the age of Cloud making infrastructure problems a thing of the past.

Grizzled techies warily eye this new promise, enumerate the pros and cons, and grudgingly conclude that there might be something to it, in some cases. They observe an economy of scale that would allow cloud providers to offer services at a lower price than spinning them up and maintaining them themselves. Perhaps the Cloud could be a good thing?

Then they spy additional services that proffer the same simplicity, but for platforms rather than infrastructure. Renting a PostgreSQL database run by someone else? That might be worth it. Using an out of the box Kubernetes? That makes sense. They have a proprietary messaging service? Okay, well I suppose…wait. Proprietary? It’s not just, say, JMS in the cloud? We have to write code that will only work on this cloud provider?

And here begins the process of scrutinizing all of the pieces of a cloud service. The calculus of what subset of cloud services offers the best combination of engineering speed, operational costs, cloud costs, and lock-in. (There must be analyst teams in each cloud vendor figuring out exactly where the line is to put the total cost of ownership for the first year just where it needs to be to achieve lock-in.)

At some point the grizzled start saying things like, “You realise that Clouds are like supermarkets? They might get you in with 2 for 1 Kubernetes, but they’ll make it back double on the logging service you didn’t think you had to be price-sensitive about.” And less grizzled techies roll their eyes and carry on.

But they say this for a reason. Some areas that Clouds cover are common, fungible commodities. Renting a server, a network, a firewall, a hard disk or even a database is relatively safe, because it is transferable to another provider.

Other areas are bespoke, and accepting them as part of a technical architecture can be a useful move, but it requires a gradual melding, like the Icebreaker technology in Neuromancer, of product and cloud vendor. The result is software that is comprised of a continuum of creations and procurements from technical product to cloud vendor technology. This is the ideal profit situation for the cloud vendor.

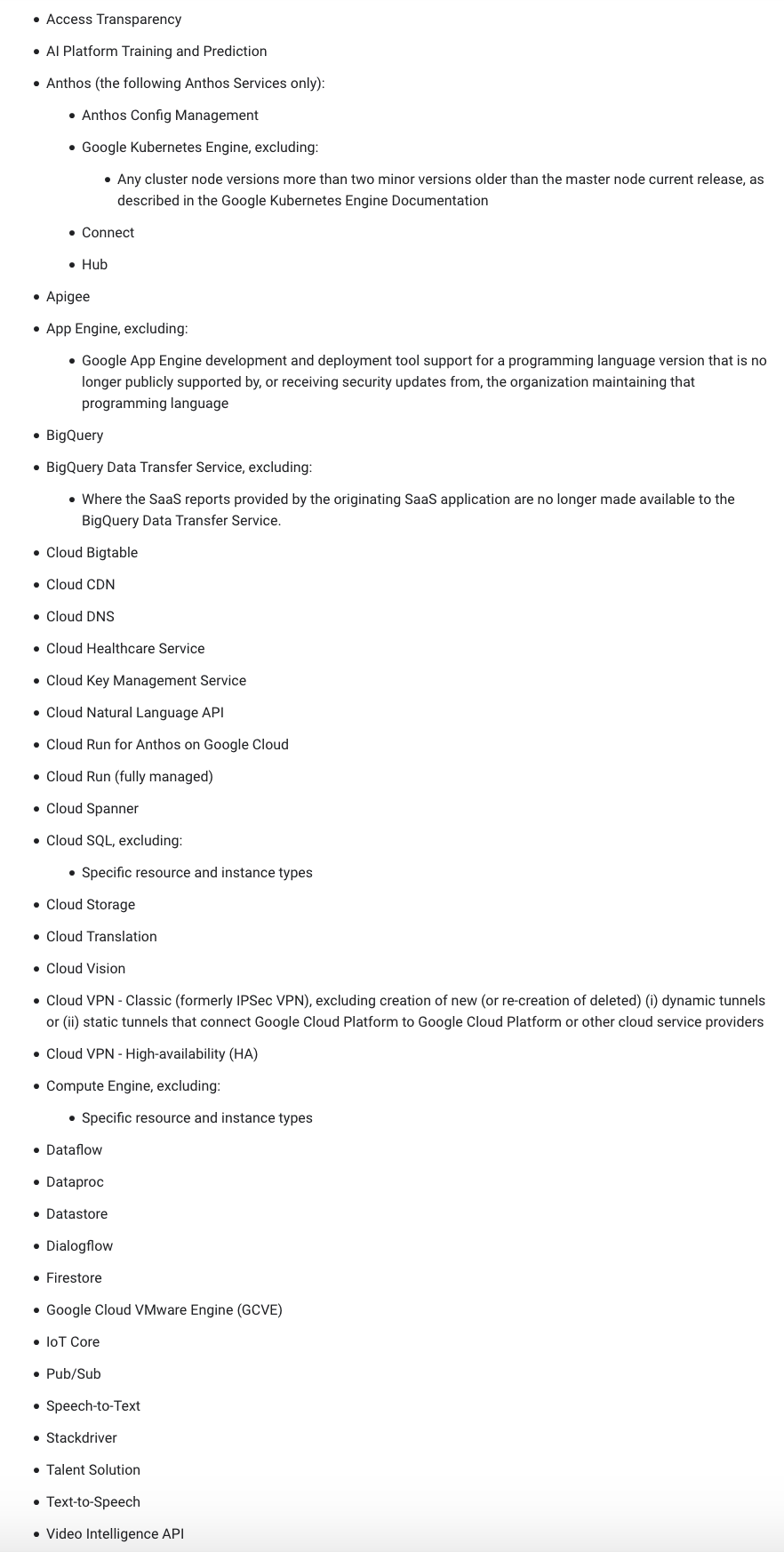

Except for Google Cloud. It appears to not be what they want at all. Products and APIs are deprecated at an alarming rate, and it’s hard to know what to build with. Renting infrastructure is fine, as is renting very standard components such as Kubernetes (although that’s also got its deprecation issues, at least it’s still an under-development product, and can be allowed more latitude). Renting some of the other services is a more fraught activity. Here’s July 2020’s deprecation list:

Just trust our cloud

Google apparently prizes perfect engineering over business sense. Other platforms have the opposite problem. Oracle Cloud is a triumph of business strategy over engineering, and despite heroic technical efforts is floundering hard as a result. Azure gets the basics right, but really, really pushes lock-in, and can’t help constantly rebranding (how long until it’s Microsoft Cloud?)

Speaking of Microsoft, there is an interesting trend arising where Microsoft is starting to heavily embrace (yes) open source software. Their Edge Web browser (soon Microsoft Explorer, Internet Edition?) is built on Chromium, with Google doing the hard yards of rendering and performance code, and Microsoft providing enterprise features on top. This means they can do the part they do best — interoperability with other Microsoft products such as Active Directory (Microsoft Directory, Active Edition?) — and get the rest free.

Similarly, Kubernetes. Looking to become the default for hosting environments, if it isn’t already, Microsoft provide a hosted equivalent in Azure. They have also released Open Service Mesh (OSM) to be fast-tracked, OpenXML-style, as a CNCF project. Coupled with Google’s slight odd behaviour around the trademark for their Istio service mesh, Microsoft perhaps have spotted an opening to be the layer in between the layer in between, so apps can be built to run in OSM, and Kubernetes becomes just another infrastructure layer. And who knows? Perhaps one day OSM will get Microsoft’s Service Fabric as an alternative backend, so Windows and Linux can be hosted, and that will of course work best in Azure.

As an alternative strategy, buying NPM and Github is interesting. Microsoft are making some clear moves to purchase entire creative ecosystems, with no end in sight.

Which is not exactly a criticism of Microsoft; it’s pretty clear what they are. It is perhaps a criticism of businesses who choose Azure, knowing this is what Microsoft are like, always teetering on the edge of acceptability, but anyway. Azure certainly makes sense for cloud-hosting Windows software. And at least they aren’t Oracle.

What is less clear is Google’s cloud strategy. Google has the technical ability to become the number one cloud provider in the world one day, if only they could decide they wanted it badly enough, and didn’t give up.

They gave up on Google+, and look at Quora and Medium and Ghost and Squarespace now. It could’ve been all of those at once, ten years ago. They gave up on Wave, and along came Slack and Teams. Google seems too scared of customers, or too unwilling to commit, to iterate, and to capitalise on their amazing ideas and technology.

And sometimes, like Goo.gl transitioning to Firebase Dynamic Links (Enterprise Edition, anyone?), it just seems completely pointless. (Is the Firebase brand the systemd-like plague of the Google enterprise, infecting all it touches with its ravening, inhuman drive?)

The grizzled techie has a stake in this. Not because of any particular allegiance (positive attitude towards any cloud provider is inversely correlated with how recently one read a news article about them) but because AWS are the strongest, and getting stronger, and every time Azure gains market share they emit a putrefying air of stifling, triumphant lock-in. Google are the underdog here. They are still frantically inventing, and creating like mad, and they prize engineering above all. That has to be a good thing. And they do not promise Easy Technology, although they do strive for As Easy As Possible. To be fair, the same is true for AWS.

But Google must recognise that a jumble of incredibly well engineered cloud services isn’t going to cut it when AWS are the default option, and Microsoft own the corporate, and increasingly an end to end dev and cloud stack as well, and both still pick and choose the best tech that Google CNCF’d for them.

Here are some closing thoughts about how Google Cloud Platform can improve its position. Some are specific to mid-2020, and all have the arrogance of the only mildly grizzled :-)

- Be the première Kubernetes cloud experience, even more than right now. Beautiful dashboards, monitoring, everything built in. Comes free with your Kubernetes offering other than the cost of the storage. Cloud Code is a great move in the dev side of this, simplifying the development process in Kubernetes. Doing the same for ops would be fantastic.

- Fix the Istio issue. The point above is what will differentiate you, not Istio’s trademark. This could be the Anthos strategy.

- Offer a Kubernetes experience that doesn’t expose nodes, such as AWS Fargate for EKS. You should be able to build this better than anyone. Maybe charge extra for cool additions such as configurable AI-driven autoscaling.

- Bless and adopt KubeMQ (or similar) and build tooling around it, so you can have a great pub-sub mechanism on Kubernetes, which is a differentiator against AWS and Azure, and doesn’t lock people in. Knative eventing looks cool, but that currently does not appear to address more “business logic” level tools such as durable queues.

Bless and adopt an in-Kubernetes Serverless technology, such as Fission. Or make your own.You did this already! Knative is Google. Try and match the experience of running Knative on GKS to the nice Google Cloud Run one.- Buy Docker. You will be able to turn the containerisation and orchestration lead into a significant advantage. Additionally, your Kubernetes-focused strategy has most to lose from Docker crashing and burning.

- Buy a CI provider, such as CircleCI. Maybe even GitLab. Integrate them extremely well.

- Get every certification/standard you can. The Deutsche Bank deal is a good sign you can play and win in regulated environments. Keep going. Health is big. Privacy Shield being dropped is big — have a good answer for this.

- Interoperate your auth with Azure AD in a point and click simple way for IT folk to set up. Give them no reason to say “Azure is just easier”.

- Copy what MS are doing to you with Chromium and Kubernetes: use the VSCode open source base to make a cloud-based IDE that makes writing (or perhaps just editing?) code for Google Cloud very straightforward. codesandbox.io use it to great effect.

Thus endeth the armchair strategizing. The grizzled are really keen to see how cloud technologies and vendors improve in the next few years, and whether lock-in really is inevitable, or even required for a successful cloud business. They also appear keen on making technology As Easy As Possible, and no easier.

Final thought: why aren’t Facebook a cloud provider?

Afterthought: if someone wants to make a website that has adverts on it, can they use the AdWords revenue to pay for the cloud hosting, and just get paid the difference (or pay the difference)? It’d be a pretty handy feature that the other cloud platforms would struggle to replicate.